Right Now with Kamyar Bineshtarigh

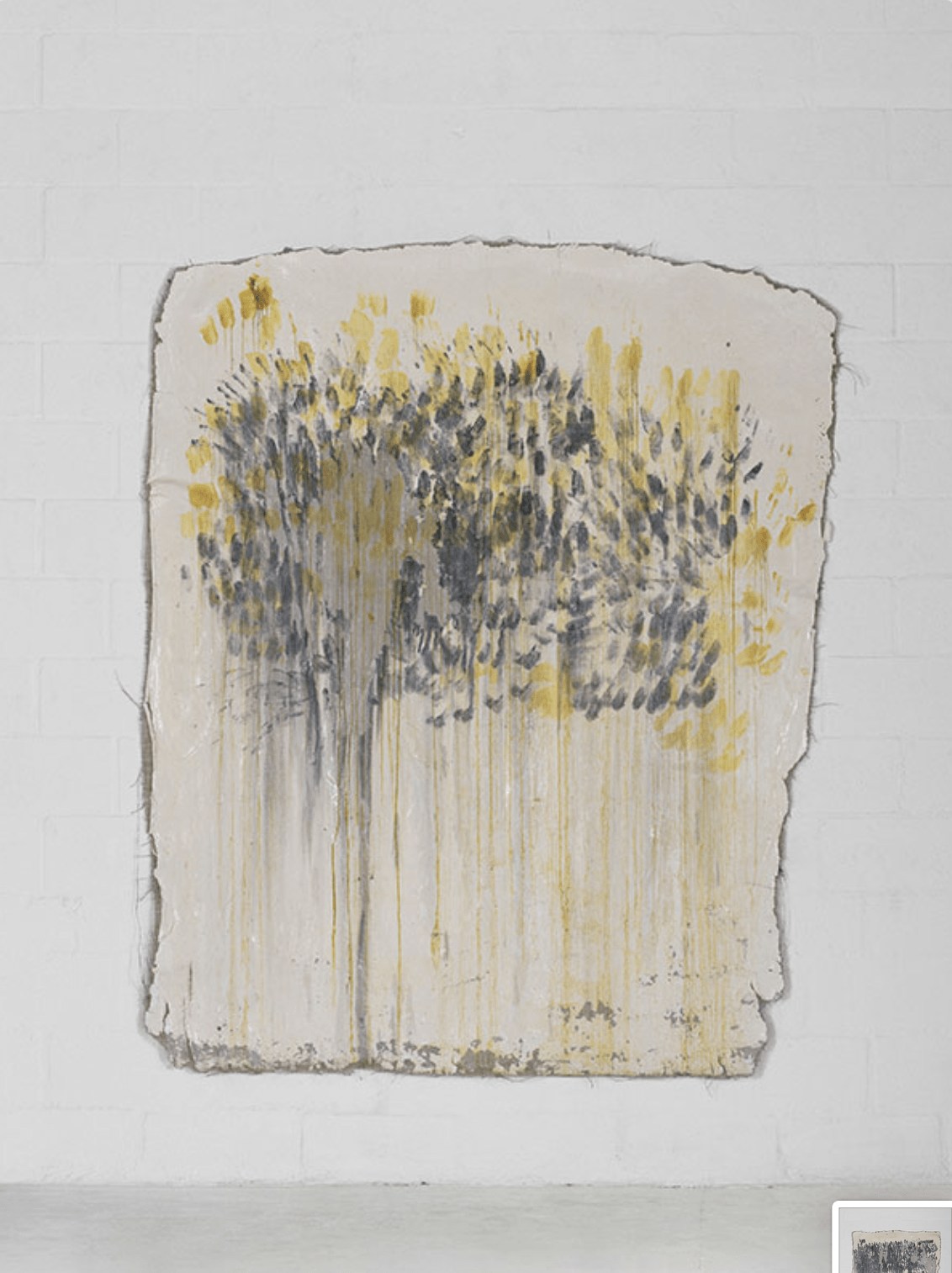

Meet Kamyar Bineshtarigh, a mixed-media artist whose recent exhibition at Southern Guild, 9 Hopkins explores the history of Salt River’s garment industry. His work reveals the handprints and years of debris carried in the walls of the building, creating a kind of ‘archive of labour’.

Salt River’s once-bustling garment industry was shut down in the ‘80s and ‘90s with the rise of cheap imports from Asia. This industry, which many depended on for their livelihoods, has created a deep fissure in Salt River’s history and contemporary climate

We asked the artist about engaging with the community of Salt River, how he sees his art fitting into the complicated history of South Africa’s garment industry, and how labour lies beneath art, architecture and all manners of making.

NK: Why were you interested in exploring South Africa's garment industry?

KB: I discovered the semi-abandoned building in Salt River when looking for an affordable studio space. Through research and conversations with my neighbours I learned more about the space and its history as a bustling garment manufacturing space in the 1930s. I then became intrigued by this history and how my art relates to the space I was working in.

NK: Could you tell us a bit about your unique medium? Why did the walls of the panel beaters shop form part of your work?

KB: Beyond working on canvas, I developed a unique method of extracting works from the walls of my former studio space. I apply multiple layers of cold glue on the walls. After drying, the cold glue forms a thickened skin that I am able to peel away from the surface. As the glue is lifted, it takes with it the underlying, pre-existing layer of wall paint from the building’s structure, along with any impressions or marks I’ve painted onto the wall. The eventual artworks also hold traces of motor oil, grit, spray paint, sweat and scuff marks. These elements archive the labour-intensive work and human movement that occurred within the space, accumulated over many years.

NK: South Africa is slowly shifting back to more local manufacturing in the fashion industry. Do you feel that what was lost can be restored?

KB: I’m not sure that’s possible. Slow fashion is still exclusively reserved for the rich. Locally manufactured and intentionally considered fashion labels are not accessible to the majority of South Africa’s consumers but rather are marketed to the wealthy few. My hope is that local labels become more accessible for people in this country.

NK: What have you learnt and discovered through working on this project in, and to some extent about, Salt River?

KB: Part of the making of these works was an exercise in creating facsimiles of the unintentional gestures I observed on the panel beaters’ walls. I now understand that a mark made in a moment of uninhibited being can never be recreated with intention. I’m still in the process of learning more about Salt River and its complex history. My research and my understanding of the area has been organic, largely realised through conversations with those who have lived in the area for many years.

NK: Salt River carries the memories and histories of culture and community, which has been marred by labour struggles and displacement. With gentrification exacerbating the erasure of this history, how do honour these memories and the people behind the labour in your work?

KB: The extracted works within 9 Hopkins that were lifted from the very walls of the panel beaters, essentially archiving, preserving and sustaining the history of the building along with the livelihoods it once held. Since the building’s demolition, the works can now be read as visceral reminders of what once was.

NK: What do you hope people take away from your work?

KB: This body of work has allowed me to intimately observe and deeply experience a space. I hope people will be encouraged to look more closely at the spaces they occupy, to think more, to consider the narratives these spaces hold and acknowledge the life and people that once preceded them. Our initial assumptions seldom allow for the nuance and intricacy of what might be truly at play.

Words by Nabeela Karim for Letterhead