Sustainable Fashion with Khensani Mohlatlole

“What am I going to wear?” is a question we ask ourselves every day.

Many of us buy our clothes from major retailers, with little knowledge of how and where they were created. But behind the glamorous veil of fashion is the gross mistreatment of workers, environmental degradation from the great surplus of clothing that gets dumped in landfills, as well as the leaking of toxins and microplastics from synthetic fabrics.

Each day, we take part in the fashion industry through the clothes we choose to buy or not buy, wear, or not wear. Whether we like it or not, we are all part of the fashion industry. As the world becomes more aware of the dark side of garment manufacturing, we're seeing a global movement emerge towards fostering better working conditions for garment workers, slower and reduced clothing production, and a renewed love for the clothes we already own.

This change is evident in the work of local designers who are embracing sustainable practices. These designers are supported by the industry at large, with South African Fashion Week and South African Menswear Week, as well as sustainable fashion activists such as Khensani Mohlatlole, who are using their platform to inspire a new, slower approach to fashion.

“I would like designers to understand that they are the beginning, not the end,” says Lucilla Booyzen, founder and director of SAFW. “For a designer to build their businesses around responsible fashion, designers have to live a life of responsible fashion.”

SAFW has been championing slow fashion brands and local design for the past 20 years. Lucilla explains that the designers showcased at SAFW all embody sustainable fashion practices, have consideration for those making the clothes and craft pieces designed to last.

“Everything in fashion begins with one idea that then ripples through the collection of a designer—it is a pure thought. This idea should reflect pure design and only from pure design can the fashion industry grow. The purer the seed the more magnificent the fruit,” Lucilla adds.

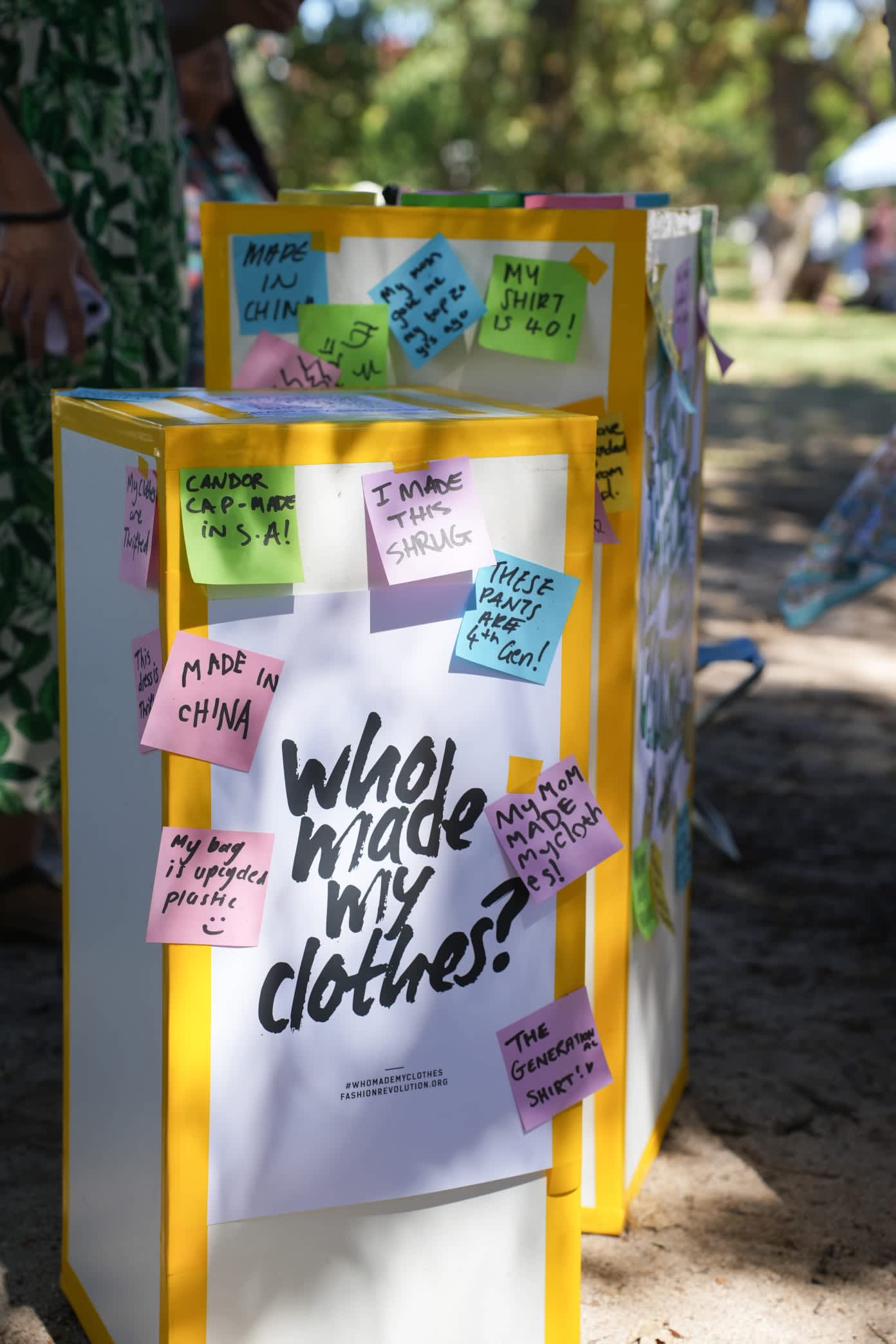

Happening alongside SAFW, is Fashion Revolution Week, taking place from 15 to 24 April. The yearly campaign supports the shift towards a kinder, fairer and more just fashion industry, hosted by the global activist organisation, Fashion Revolution.

As the theme for this year’s campaign is ‘How to be a fashion revolutionary’, we spoke to Khensani Mohlatlole to learn more about what this means and how we can transform our fashion industry.

“To be a fashion revolutionary is to be someone who realises how getting dressed is a communal act,” says Khensani. “It’s not only about considering and caring about the labour conditions, but it’s also about celebrating the skill, tradition and care that goes into making clothes. And we carry that care on through looking after our items, making them last, and ensuring they find a good home once we’re done with them.”

NK: Sustainability, especially when it comes to fashion, is a highly contested term. What does sustainable fashion mean to you?

KM: To me, it means consuming and producing fashion in a way that's better for people and the planet. I think a lot of people separate concerns for the environment from a concern for people, even though people are a part of the environment. Sustainable fashion affects so many parts of life; from protecting and nurturing the natural world, ensuring people have safe working conditions and are able to afford a good quality of life, and, on the consumer side, having high-quality clothing that's made to last.

NK: How do you incorporate sustainable fashion practices in your everyday life?

KM: Most of all, I aim to buy less or not at all. I've learned about proper laundry care and mending to ensure the longevity of my clothes. I often opt to purchase secondhand when I do buy, or from transparent brands that are working towards ethical production, such as The Bam Collective or Fashion Students Archive.

I take the time to interrogate trends and why I'd like to buy into them. And when I do consume clothes, new or secondhand, I weigh how a garment will fit into my life, how much I know about how it was produced, and what would happen once I was ready to let go of it.

Khensani has grown a large following on social media for recreating Victorian-style clothing. “I really admire the rigour and discipline with which this style of clothing was made,” Khensani explains. “There was a lot of detail when it came to making clothes last longer, and the people themselves were a lot more knowledgeable around garment care and mending in a way that we aren’t anymore.”

NK: What do you hope to see change in the local and global fashion industry?

KM: South African garment workers are much more protected than workers in places such as Bangladesh and China so I'd like to see more South African brands producing locally. Local production not only means we would be stimulating our own economy but, as consumers, we can have peace of mind that our clothes were made in better conditions.

Globally, we need to invest more resources into tackling the mass of textile waste that disproportionately affects the Global South.

As threats of climate change loom over us, sustainability becomes a greater demand from consumers. But, in addressing these demands, many fashion brands use sustainability as a marketing tactic to create a facade that a brand is doing more for the planet than it actually is, often referred to as greenwashing. From clothing donation initiatives to recycled fabrics, greenwashing has made navigating sustainable practices hazy and complicated. “It robs people of their agency to play their part and feel like they can affect change,” Khensani says.

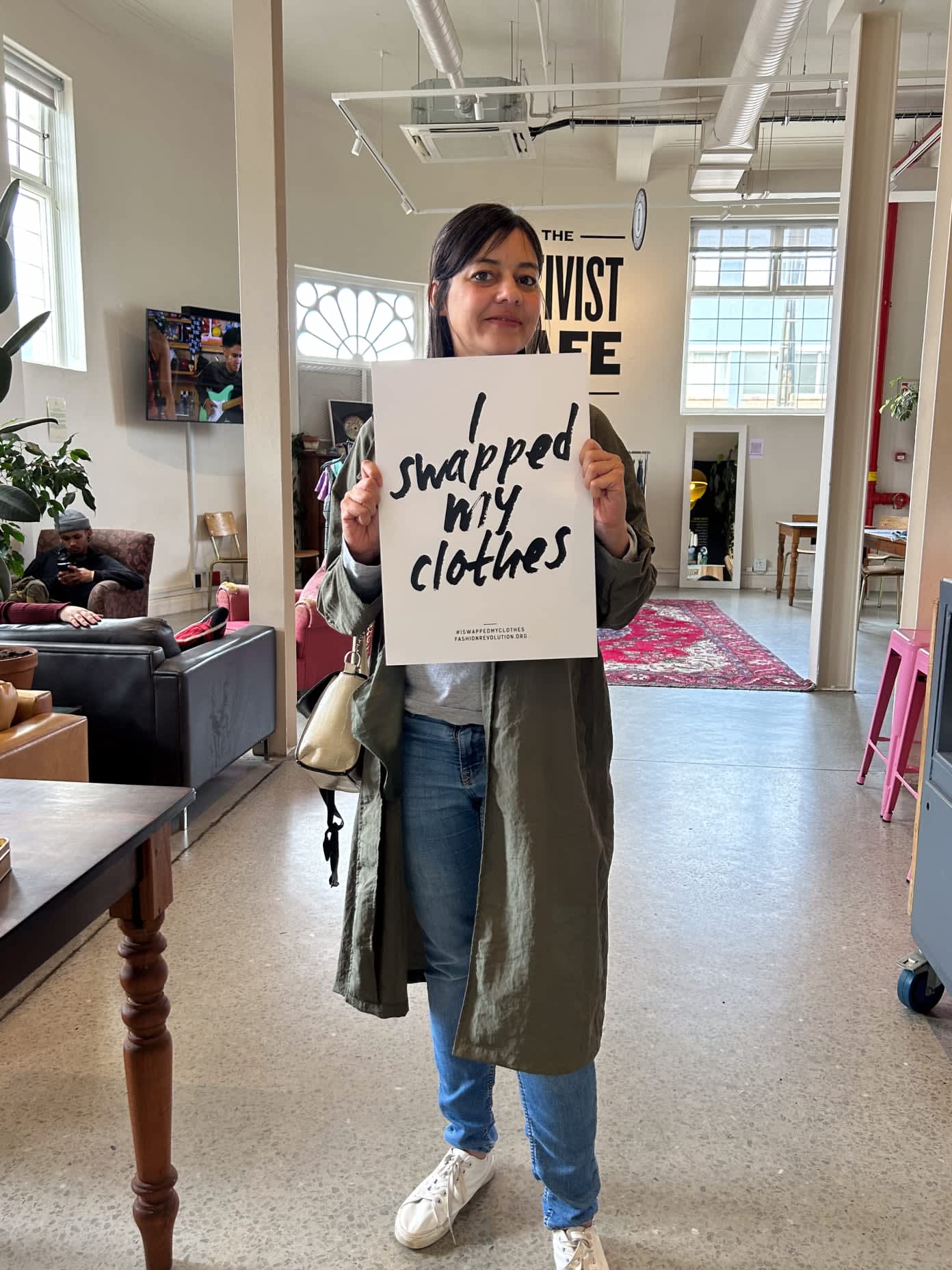

The South African branch of Fashion Revolution will be hosting a range of events and activations, from film screenings to swap shops, to educate and inspire people to take action against the harmful nature of the fashion industry.

Words by Nabeela Karim for Letterhead